The following was written and turned in as a class project

by Charles Steven Christine.

He used a tape recorder to interview his father (Charles Richardson Christine)

about his WWII experiences aboard the submarine USS Dragonet.

Reprinted here with his permission.

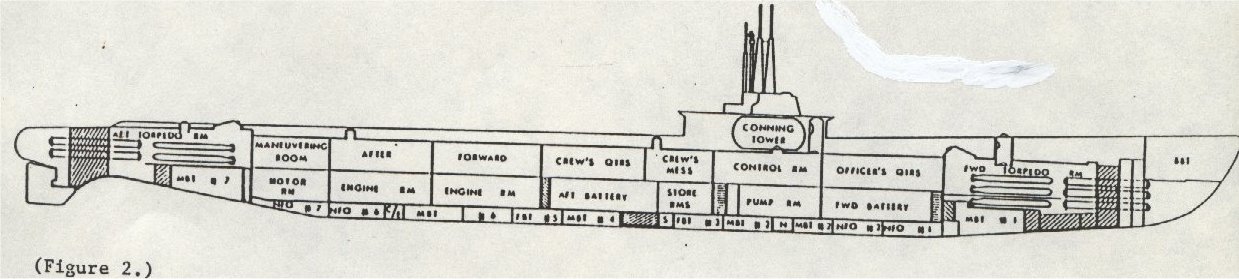

During world war II every young able-bodied American male felt compelled to serve his country by enlisting in the armed forces, and I was no exception. I enlisted in the United States Navy, in 1942. After completing basic training and electronics school, I was assigned to a newly built submarine called the U.S.S. Dragonet, SS 293 The name Dragonet comes from a family of fish found in the warm seas of the world. She was built at Cramps Shipyards, Philadelphia, in 1943, and commissioned March , 1944. The submarine, a Balao Class, was 311 feet long and 27 feet wide with the most up-to-date equipment installed for the times. (See Figure 1.)

The operating depth of our class

of submarine was 400 feet, an increase of 100 feet deeper tan the previous class

of submarines. This was accomplished by shifting from mild steel to high-tensil

steel and increasing the thickness of our pressure-hull plating. We could carry

a maximum of twenty-four torpedoes, accommodating six bow (front) tubes and four

stern (rear tubes. The crew consisted of ten officers and 70 to 71 enlisted men.

During the war the mess cooks for the officers were either Negro or Philippine.

There were two Negro mess cooks on board our particular submarine. They also had

double duty as lookouts on the periscope shears, the uppermost area of the

submarine. The maximum surface speed was twenty knots and submerged was nine

knots. Our normal submerged depth was 100 feet traveling at two to five knots,

only rising to sixty feet for periscope depth. Thee were several reasons for

cruising at only two knots; at sixty feet the periscope creates a ripple

resembling a feather on the surface of the water, at a greater speed the

periscope would create a larger feather and increase the ease of detection; and

a submarine is a search and destroy vessel slowly hunting its prey. I was

radioman 3rd class stationed aft (rear) of the control room, designated the

radio room, while the submarine was on the surface, and in the conning tower

using the sound gear listening for propellers, or as they are referred, screws

of other ships, while the submarine was submerged. (See Figure 2.)

While on route to Pearl Harbor via Key West Florida, the captain, Commander Jack H. Lewis, decided to test dive the submarine. During the descent the captain had remembered that the quartermaster was left on deck, and we surfaced immediately. The quartermaster was found swimming around the Atlantic Ocean wet, but unharmed. When he got aboard he said, "I climbed as high as I could go, and then swam off." I thought to myself, could this be a premonition of what the future holds in store or was this just an innocent mistake?

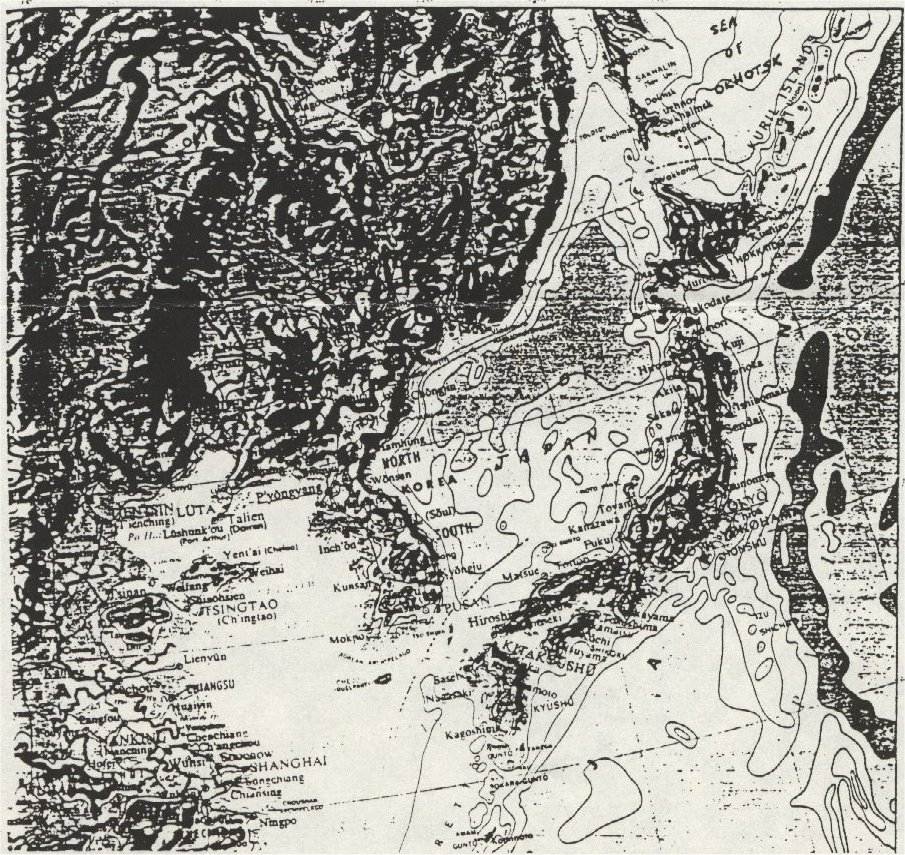

The U.S.S. Dragonet rreached Pearl

Harbor, October 1944 and was put out for her first patrol, November 1st, bound

for the Kurile Islands and the Sea of Okhotsk. (See Figure 3.)

Our orders were to search and destroy any and all Japanese vessels. There were four sound men working in shifts of four hours on, and eight hours off. It was so cold that one evening, while on duty, it was necessary for me to go on deck to break the salt ice off of the antenna because it was so heavily encrusted. We would patrol submerged during the day and surface at night to charge the batteries on board the boat. One evening we stayed too long on the surface, and as dawn was breaking, the Japanese were signaling our ship from an island thinking it was one of theirs, we immediately submerged as the captain yelled, " DIVE, DIVE, DIVE!".

It was approximately 8 O'clock, on the morning of December 15, 1944 operating the sound gear while submerged south of Matsuwa, Japan, I reported to the officer of the deck, " Mr. Johnson, I have contact with screws at heading 038 degrees." He informed the captain, and we rose to 60 feet to survey the area and found nothing. The sound heads, eighteen inches in across attached to a shaft eight inches in diameter, were located in the forward torpedo room underneath the submarine. Hydraulically operated, the mushroom shaped sound gear would suspend through a hatch two feet below the vessel. I kept hearing the sounds of propellers all around the submarine. Again I reported this to the officer of the deck. We rose to periscope depth for a second time and found nothing. On our decent to 100 feet there was a bump, bump like hitting a car stop at the local grocery store parking lot. Then there was a horrible screech of steel being ripped apart. We discovered we had struck and uncharted submerged pinnacle which pierced our pressure-hull on the port (left) side of the forward torpedo room. The sounds that I reported were the sounds of our own propellers reflecting off of the coral formation. Fortunately, there were only three men in the forward torpedo room at the time of the collision. The last man out was running through hip deep ice water before the other men secured the water tight door. The sound gear was destroyed, so I descended through the conning tower and manned the electronics in the radio room. The boat was in 80 feet of water, and the captain gave the order to fill the ballast tanks with compressed air. This only resulted in getting the stern to rise completely out of the water, putting the submarine at a 48 degree angle. Commander Lewis then gave the order for all off duty personal to go aft to help raise the bow. With no success the captain said " Abandon Ship!". This would have meant that the crew would have to go to the surface using a device called the Munson Lung before reaching the surface we would have frozen to death in the ice cold water. The captain and the executive officer consulted and decided to blow water out of the flooded compartment with compressed air. At 8.45 A.M. she surfaced just four miles from the airfield at Matsuwa. We set course for midway island, to clear the danger area as quickly as possible. We were committed to the surface. The crew was ordered to battle stations for fear of an air attack. I was ordered to transmit a message requesting assistance this request was denied. Luckily, there were no serious injuries and we were never confronted by the enemy.

Our determination and skill was further tried when we had to run through two days of storm due to a typhoon. I was sitting in the crew's mess, on the second night of the storm, drinking a cup of coffee. All of a sudden a wave slammed into the boat broadside listing it 63 degrees to port. On the starboard side of the mess there were two sinks filled with water, when the boat rolled from the force generated from the impact, the water flew out of the sinks, clearing the passageway and the first table, drenching the second table secured against the bulkhead (wall). Throughout the submarine men were thrown out of their bunks, and objects propelled like projectiles being fired from a cannon. It seemed like an eternity, but the water in the forward torpedo room finally shifted to the opposite side bringing the vessel back to its upright position. One of the black mess cooks, standing lookout duty, was literally hanging on the railing of the periscope shear as his feet were dragging in the water. After he was relieved of his watch, he came below and said " I done lost twenty years off my life!".

We finally arrived at Midway Island and secured the submarine to the pier. No one was killed or seriously injured from our ordeal. Everyone went to the barracks for a well-deserved night's rest. The next morning the officers, one cook and a machinist took the boat to dry dock. The submarine was placed in an enclosed docking area and the doors were locking in placed. The water was the drained out of the area, and the boat rested on the holding chocks. This was the first time the crew really got to survey the severity of the damage. There was a jagged hole approximately twelve to fifteen feet long on the port side of the torpedo room. I could see a mattress hanging lifelessly halfway out of the cavity. We were the only submarine to have its forward torpedo room completely flooded, list 63 degrees to port without capsizing and be able to return to tell the tale. This is certainly an adventure I will never forget, but would never want to relive.